Spotlight Q & A with Professor Jeff Dangl

Professor Jeff Dangl is the John N. Couch Professor of Biology and HHMI Investigator at the University of North Carolina - Chapel Hill. He currently serves as a member of 2Blades’ Scientific Advisory Board and is a member of the reviewing editorial boards of Science, Cell, and a former member of several other journal editorial boards. The Dangl lab at UNC-Chapel Hill has contributed significantly to the use of Arabidopsis genetics as a tool to analyze plant-pathogen interactions and is funded by HHMI, the NSF, and the DOE.

Dangl was elected to the UK Royal Society in 2024, the American Academy of Microbiology in 2011, the U.S. National Academy of Sciences in 2007, and the German National Academy of Sciences (Die Leopoldina) in 2003. In 2025, he was awarded a share of the Wolf Prize in Agriculture “for groundbreaking discoveries of the immune system and disease resistance in plants." Watch the awards ceremony HERE (the Agriculture Prize begins at 6:08).

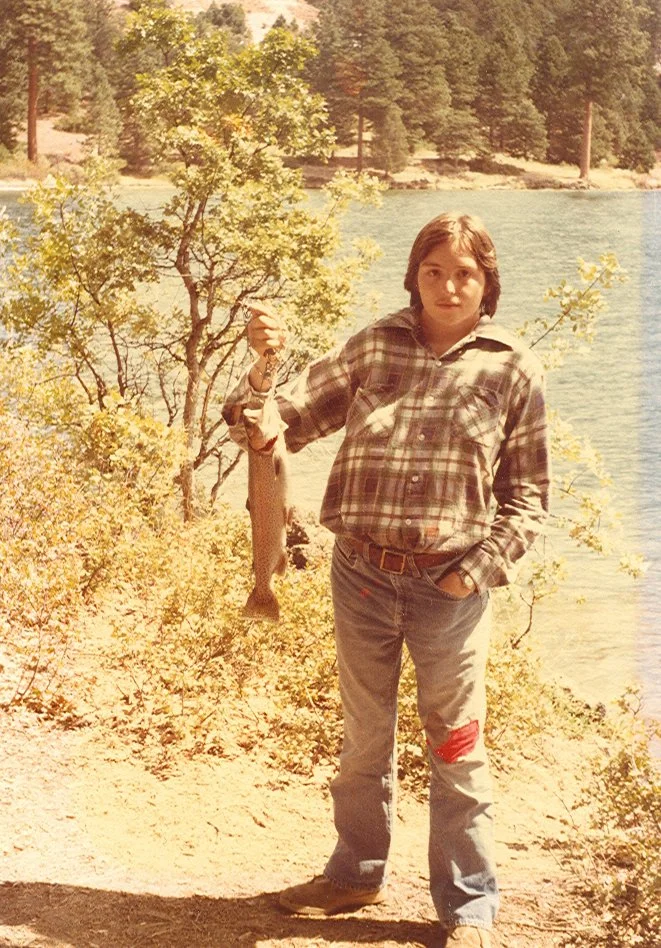

Jeff trout fishing on the Upper McCloud River in CA, mid 1970s.

What motivated you to pursue a career in biology, especially plant disease research?

I grew up in a small town in northern California where I did a lot of bird hunting and fishing. At one point in 2nd grade, my father cut open a salmon to see what it had eaten, and we noticed the heart was still beating. While this is admittedly pretty grotesque, my first impression was that biology was amazing.

As I grew older, my interest in wildlife and biology only grew. When I went off to college at Stanford, I discovered molecular biology as a 2nd year university student in 1977. It was the beginning of the recombinant DNA and gene cloning era, and some Stanford faculty were at the forefront of this work. The pioneers of this era were also my teachers, and I was completely smitten by the idea of understanding how basic cellular functions were encoded in genes and genomes.

At the time, I was studying molecular biology and genetics and was handing out single page CVs in faculty mailboxes begging for a summer job so that I didn’t have to go back to my small town for the summer. I was interested in trying my hand at research.

Ron Levy, a noted oncologist, invited me to his office and said that while he didn’t have any money to hire me to work in his lab, he suggested that I talk with Leonard Herzenberg, one of the leading immunologists at Stanford. Len was kind enough to offer me a job on the spot. I was fortunate enough to work in the Herzenberg lab, initially as a Fluorescence-Activated Cell Sorter operator in the late afternoons and evenings and later as an undergraduate learning the basics of cellular immunology and flow cytometry from Sam Black, who had a distinguished career at the International Laboratory for Research on Animal Diseases (ILRAD) in Kenya and at UMass, Amherst.

I eventually switched to my own project, under the tutelage of Vernon Oi, who first expressed engineered immunoglobulin genes in transfected lymphoid cells. This led to the many therapeutic monoclonal antibodies used today to treat human cancers and other diseases. I isolated hybridoma clones that produced all possible mouse immunoglobulin heavy chain genes in combination with an identical antigen binding site. I continued this research during a gap year in the Herzenberg lab and then chose to stay at Stanford, and in the Herzenberg lab, for graduate school.

Jeff and his wife, Sarah Grant, enjoying a beer at the Max Planck Institute in Cologne, Germany, 1993

One day, Vernon Oi asked me to find a PNAS paper (e.g. walk to the library and make photocopies) that was relevant for our work constructing chimeric immunoglobulin molecules to make copies for him and me. As I was thumbing through that (hard copy) journal, the page fell open to a paper written by Klaus Halhbrock’s lab, then in Freiburg, Germany. This paper described transcriptional responses in cultured parsley cells to fungal extracts. Plant cells were shown to undergo gene transcription changes consistent with changes in their secondary phenylpropanoid biosynthetic capability. In that paper, there were references to something called the “gene-for-gene” hypothesis which described specific disease resistance responses triggered in certain plant genotypes by certain pathogen genotypes. I read a bunch of papers on the subject and was fascinated. I realized there must be specific recognition and at least one receptor system that controlled how these gene-for-gene interactions functioned. The concept of receptors as lynchpins in the gene-for-gene hypothesis was a new idea at the time being pushed by Noel Keen, among others. The simplest hypothesis was that there must be a plant immune system of some sort that would be capable of recognizing molecules derived from pathogens of all classes (viruses, nematodes, fungi, bacteria). I found this to be incredibly exciting.

So, thumbing through a random paper by Klaus Hahlbrock is how I got into studying plant defense. My experience in mammalian immunology allowed me a different perspective when pursuing a career in plant defense and equipped me with a new way of thinking and interpreting plant disease resistance research.

It is important to note that up to this point, I didn’t know anything about plants. I had not taken a single class in plant biology.

At the same time, my girlfriend (now wife), Sarah Grant said to me “if you want to be with me after school, you need to find a reason to come to Cologne, Germany because I’m going to do a post-doc at the Max Planck Institute for Plant Breeding (MPIPZ).” I lucked out and found a post-doctoral position with Klaus Hahlbrock (who had just moved to the MPIPZ), funded by the US National Science Foundation to encourage people from other fields to jump to plant molecular biology.

And the rest, as they say, is history…

You were recently awarded the Wolf Prize in Agriculture, alongside fellow 2Blades SAB members Brian Staskawicz and Jonathan Jones. What does this recognition mean to you, both personally and professionally?

Personally, it’s a huge honor to share it with Jonathan and Brian. I met these guys when I was a post-doc in 1987 or 1988, and later when I was starting my first lab, they were already quite established and were very generous with their time and advice.

These kinds of awards are always longevity and are ‘community awards’ in the end. This award (at least my share of it) was the result of the 33 grad students and 80 post-docs who did the work in my lab. I’m pleased that they were honored and their efforts recognized.

Sarah and I strove to build our first independent groups in Cologne to focus on defining creative research directions, practicing careful experimental design, and experimentally establishing causality using genetics. We didn’t micro-manage interactions within and outside the lab and we tried to build a community based on giving openly our reagents, seeds and other resources. We hoped to push science forward with the idea that we would all get credit eventually.

Another aspect of the Wolf Prize that resonates with me is that one of the earliest winners of the Wolf Prize in Medicine in 1981 was Stan Cohen, one of the creators of recombinant DNA. Stan was Sarah’s PhD advisor and was a kind mentor to our entire cohort of graduate students. And then in 1990, Jozef “Jeff” Schell, who co-discovered the mechanism of T-DNA transfer that led to the first transgenic plants, was awarded the Wolf Prize in Agriculture. Jeff was a very important figure during both my time as a post-doc at the Max Planck and as a junior group leader at the neighboring Max Delbrueck Laboratory in Cologne.

What do you see as the most promising (and /or concerning) parts of AI as it relates to the future of science and plant disease research?

I’m not an AI expert, so I’ll give you my observations and wish list.

My not so brilliant observation is that AlphaFold has revolutionized protein structural prediction and drives experiments that would have previously taken years to intuit. The fact that you can predict protein structures and protein-ligand or protein-protein interactions from primary amino acid sequences answers an ~70 year old riddle that stumped even Linus Pauling. So, I think AlphaFold and the ability to scale and analyze protein to protein, and protein to small molecule interactions is changing every field of molecular biology, including NLR design and NLR function. So, that kind of thing is amazing.

Within the agricultural biologicals field, the ability to predict secondary metabolite functions in microbial genomes is on the way (not perfect yet) but it’s getting there. That will be an important use.

There are undoubtedly uses in things like modeling micro-climate changes across agricultural growing space. I can imagine a day when corn farmers in Iowa can rely on AI to micro-manage their fields using machine-learning algorithms to determine when to spray, when to use fertilizer, etc. This may already be happening to some degree.

However, science requires good, considerate writing and I think that it clarifies our minds to write things up ourselves. I strongly believe in developing good writing skills as a key aspect of scientific training.

What advice would you give to young scientists just starting out in their career?

There is a lot of fear in the US currently, and debate over whether science is a good career, given the obvious war on science and independent thought being waged by the current administration. My advice is to follow your passion and don’t worry about the job market, because excellent scientists who are passionate, creative and technically adept will always get a job. You may need to leave home to do it, and you may need to move and be intellectually flexible to stay on the cutting edge, but these are key features of a life in research, not bugs.

Aside from that, I think it is critical that young scientists develop and place great value in independent thought. Don’t follow the mob or base your research directions on the latest trend on Twitter (X) or BlueSky. Think. Read original papers deeply (please!). Think more. Discuss openly with colleagues and seek criticism. Revise your ideas. Test them. Fail. Develop a thick skin. Repeat.

The MPMI field is now nearly 50 years old, so there is a lot out there and a lot of interesting questions from 40-50 years ago that are still unsolved but are not in the headlines today. Find one of those and create your own path. There are always hidden gems in the literature if you read it with an independent mind and are not necessarily glued to today’s dogma. Don’t misunderstand me — today’s dogma is dogma because it is generally based on solid data and careful interpretation. But it is not eternal and needs to be constantly challenged.

“Renoir a m’ a dit: Quand j’ ai arrangé un bouquet pour le peintre je m’ arrète sur la côté que je n’ avais pas prévu.

(Renoir told me: When I have arranged a bouquet for the purpose of painting it, I always turn it to the side I did not plan)

- Henri Matisse, Jazz”

It sounds like during the time you spent as a post-doc and junior Group Leader, the mentorship you received was foundational to your career. Is that still the case or has the need for mentored periods in science shifted over time?

If you want to be a PI and lead a research group, then you need a PhD and to spend time as a post-doc. If you don’t care to lead a research group, then there are many ways to have a career in science. Each requires some level of mentoring.

For me, being a post-doc embedded into a structure was instrumental because I completely changed fields. During my post-doc in the Halhbrock department I benefitted immensely from the wisdom of Imre Somssich, Wolfgang Knogge, the late Dierk Scheel, Csaba Koncz and graduate students like Paul Schulze-Lefert. Similarly, as a junior Group Leader down the hall from these folks and from the Schell department. If I didn’t have the group leaders in those departments around me, I would have failed. But one needs to be willing to be assertive and seek advice. Don’t wait until someone establishes a ‘mentoring committee’ for you. Go out and build those relationships. Don’t be afraid. People love to discuss science and give advice. Your job is to seek a broad set of opinions and filter them to apply to you and your goals.

Aside from seeking mentorship, it is important to educate yourself and appreciate that running a research lab is a different skillset from being a bench or computational scientist. So, being adaptable is critical to bringing new insights into the field and to your team.

Jeff and Sarah Grant, taken from their backyard in North Carolina, 2019

You serve on 2Blades’ Scientific Advisory Board. What attracted you to 2Blades?

I’ve been involved in 2Blades nearly since its inception in the early 2000s. I was attracted to the other individuals associated with the organization. 2Blades is known to have very smart people associated with its work, both in the past and today. The thought of bringing NLR biology and technologies forward to benefit developing countries was extremely attractive to me - and still is. That a small independent group can bring together thoughtful collaboration in the way that 2Blades has done is very rewarding.

The primary reasons that attracted me to 2Blades: people, topic area, philosophy.

What do you enjoy outside of work?

We live on 3 acres of forest in North Carolina, and I enjoy watching the seasonal changes and the migration of birds. I was never much of a bird watcher growing up, but now enjoy it a lot.

I also read a lot — especially history and fiction. In addition to immunology, I was also an English major in college, so I need to feed that side of my brain as well.

Lastly, It’s been said that I enjoy a good meal, good wine and scintillating company.

I hear you also enjoy good music. Is there any relevance to your musical tastes and your career path or interest in science?

I will answer that with a Grateful Dead lyric:

“Once in awhile, you get shown a light

in the strangest of places if you look at it right.”

That sums up my career.

Final thoughts:

I have been very lucky in my career, dating back to when I serendipitously shyly entered Len Herzenberg’s office, randomly stumbled onto the PNAS paper from Klaus Hahlbrock’s lab, took Jeff Schell’s suggestion to apply for a Group Leader job, or was lucky enough to meet my Wolf Prize co-winners and dear friends, Brian and Jonathan. But luck is when serendipity meets a prepared mind. The “aha moments” come to prepared minds. The way you prepare your mind is to be an avid reader, discussant and digester of science, seek out big questions in science, think for yourself, be willing to share your untested ideas with colleagues and get critical feedback, iterate those ideas and then try to design the perfectly controlled experiment. I have tried to do that throughout my career, with mixed success.